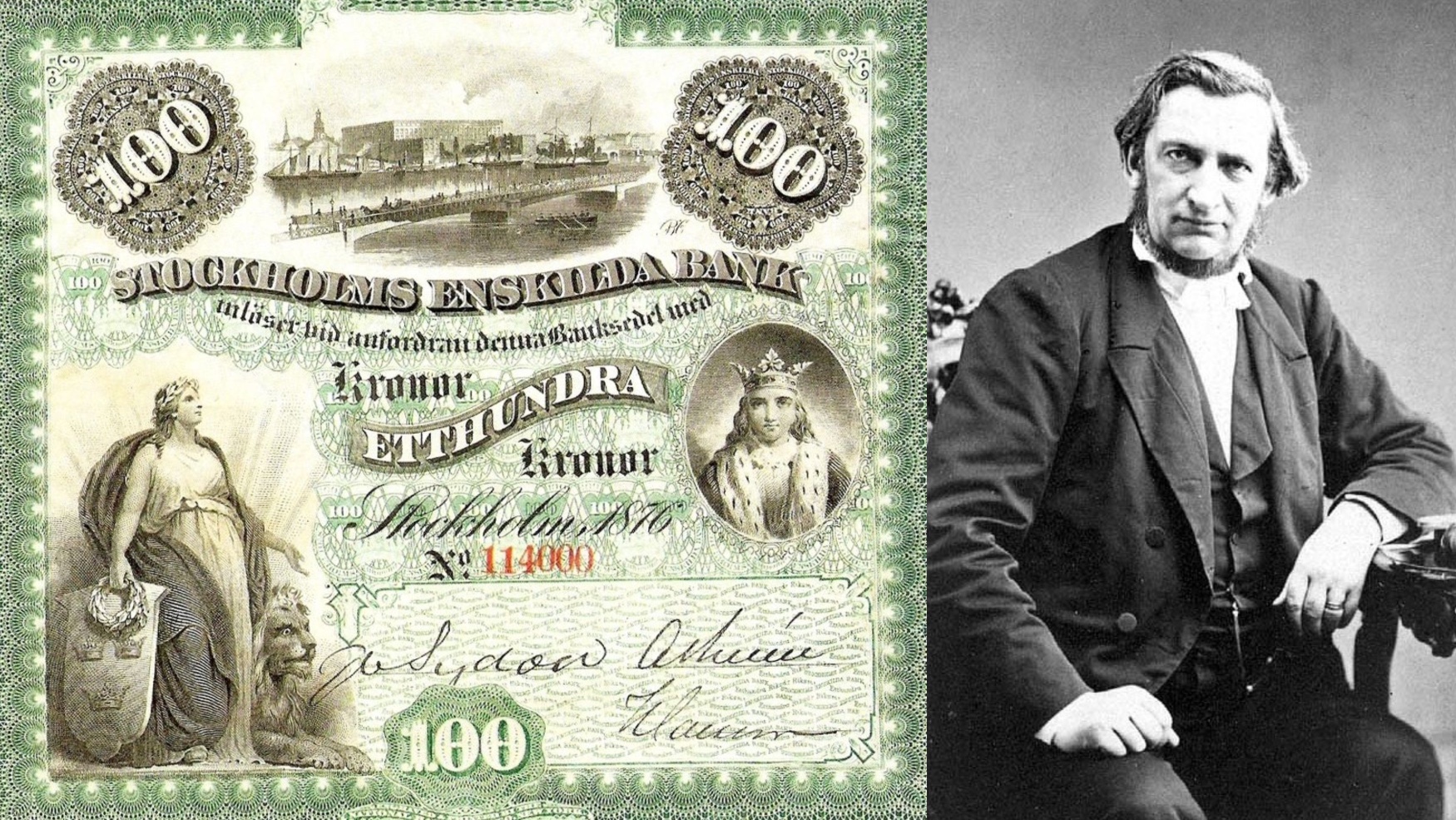

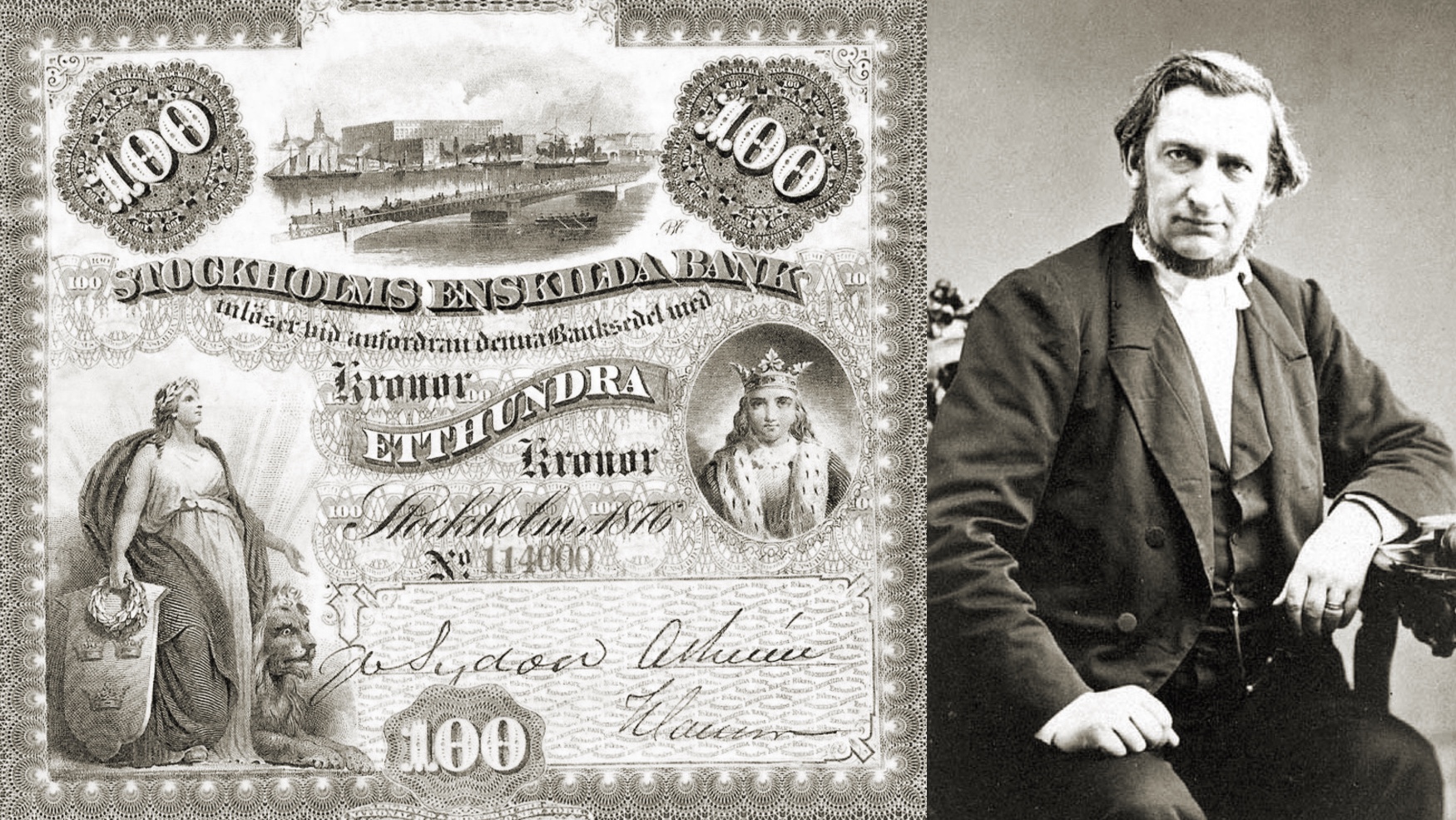

Raoul Wallenberg was born in 1912 in Stockholm. The Wallenberg family was one of Sweden’s most famous and influential industrialist and banking families. Raoul’s great-grandfather André Oscar Wallenberg, who was a business man, navy officer, publicist and member of parliament, had in 1856 founded Stockholms Enskilda Bank, which was Sweden’s first privately owned bank and laid the foundation for the mighty Wallenberg empire. Raoul was raised to become an ‘independent and responsible world citizen’. But it was not as a businessman or a banker that Raoul would attain world fame.

As Raoul’s father tragically passed away a few months before he was born, his grandfather Gustaf Wallenberg came to play an important role in his upbringing.

Gustaf was a businessman and a diplomat, and already as a child Raoul got the chance to travel abroad to visit his grandfather, for example to Istanbul in Türkiye.

Before graduating from high school, Raoul spent a few months in the small city of Thonon-les-Bains in France attending a language course. There was a younger Jewish boy from Hungary attending the course there as well. He was physically smaller than the others and was being teased and bullied. However Raoul did not join in with the bullies; instead he protected the boy and became his friend.

Raoul’s grandfather insisted that he should complete his university studies in the United States, which was rather unusual for a Swede at that time. Raoul spent four years at Ann Arbor University in Michigan, majoring in architecture. During the summers he hitchhiked around the US, exploring the country. One time he ended up in a car with an armed gang who drove him out into the woods where they robbed him. Raoul managed to stay calm and even convinced the robbers to drive him back to the main road. Later he remembered the incident as a ‘very interesting experience’.

After finishing university Raoul went to South Africa to complete a traineeship. Although he was raised during a time when ‘racial theory’ was part of the general discourse, he soon became appalled by the racism he was witnessing.

Raoul continued his education by working in a bank in the city of Haifa, located in what was then the British Mandate for Palestine. There he acquired many Jewish friends who had fled Germany after the Nazi takeover in 1933.

In the late 1930s Raoul was back in Stockholm looking forward to a career in the family bank. However the family were reluctant to give him a major role, as he was considered to be too extrovert. Raoul has been described as funny, charismatic, and creative, which were not very typical virtues for a banker at that time. Instead of joining the bank, Raoul got involved in a food importing business that had been founded by a Hungarian Jewish refugee. The company imported various Hungarian food products, for example the famous Rex ketchup. Raoul went on several business trips to Hungary where he established a broad network.

In September 1939 the Second World War started. In the following years around six million Jews, half a million Roma, and many tens of thousands from other groups considered to be ‘inferior’ were killed by the German Nazis and their collaborators. Hungary was an ally of Germany, but the Hungarian Jews were not deported during the first years of the war. This all changed in March 1944 when German troops occupied the country. In just a few months in the spring of 1944, the German SS together with their Hungarian collaborators deported around half a million Jews from Hungary to Auschwitz and other extermination camps.

The pace and brutality of the Hungarian Holocaust shocked many, and in the US it was decided to launch a rescue operation for the Jews of Budapest who had not so far been deported. The US and the Swedish governments agreed that the operation should go under the Swedish flag, since Sweden, as a neutral country, still had diplomatic representation in Hungary.

It is late summer in 1944, and hundreds of people are queueing outside the gate to the Embassy of Sweden on Gellért Hill. They are waiting to apply for a Protective Passport – a ‘Schutzpass’. For many, having a Schutzpass will mean the difference between life and death.

Raoul’s activities grew at a rapid rate and after only one month in Budapest he had hired 70 coworkers. He soon needed more office space, and he was able to rent two floors in the villa next to the Embassy that was owned by the Zwack family, the producers of the famous Unicum liqueur.

In November 1944, the Hungarian authorities established ghettos where the Budapest Jews were confined awaiting deportation. Thanks to intense lobbying from Raoul and other international diplomats, Jews holding protective passports from neutral states were concentrated in an area bordering the Danube, north of the Margaret Bridge. The area became known as ‘the international ghetto’.

During the autumn of 1944, Raoul’s humanitarian operation grew and became more and more complex. Raoul, who by now had more than 300 coworkers, organized daily food deliveries to the families hiding in the safe houses. He even managed to set up a functioning hospital with 50 beds.

At the end of November 1944, around 17 000 Jews were gathered at the Józsefváros Railway Station awaiting transportation in sealed cargo wagons to Germany. Raoul rushed to the train station and demanded that the Jews under Sweden's protection should be released. He set up a table on the platform with a thick binder and randomly started to call out typical Jewish names.

In January 1945, the Soviet Red Army entered Budapest and on 16 January the Jews in the international ghetto were freed by Soviet troops. Raoul Wallenberg’s mission in the Hungarian capital was over. But Raoul did not plan to stop his work. He wanted to continue to help the Hungarian Jews in the period after the war.

We do not know exactly what happened to Raoul after 17 January 1945. His briefcase stands abandoned on a bench, but its owner is missing. Raoul never came home to Sweden. He never got to meet his family again and he never got the chance to meet the many thousands of people he had managed to save from the Nazi scourge.

Click on each point to read more about Raoul Wallenberg's stay, activities and legacy in Budapest.

Use the slider to control the opacity of a contemporary Budapest map from 1944. Click on the blue points to see more sites related to the story of Raoul Wallenberg.

The Holocaust could happen because the majority of the population stayed silent. Most people were not Nazis of course, but they became passive bystanders. But during this time of horrendous evil and inhumanity, there were a number of individuals who dared to go against the stream and tried to help their fellow humans. It is our duty to remember these heroes. But it is even more important to follow their example and be inspired by their courage and humanity.

Raoul was a hero, but he did not act alone. He built up an organization of around 300, mainly Jewish, coworkers, and he got active support from all the other diplomats at the Embassy of Sweden. Diplomats from other neutral countries also had their own rescue programs and cooperated with Raoul.

There are also many examples of Hungarians who risked, and often sacrificed, their own lives to help their Jewish compatriots. These were army officers, policemen, priests and civil servants who used their influence to help Jews. But there were also many ordinary people who helped by hiding their Jewish neighbors.

It is important to remember the heroic deeds of Raoul and the others who save lives – but it is even more important to follow their example. Together with partners such as the Raoul Wallenberg Association, the Raoul Wallenberg House of Humanity, and the Swedish Raoul Wallenberg Academy, the Embassy of Sweden in Budapest supports a number of programs and projects that aim to pass Raoul’s legacy on to the next generation.

'In the footsteps of Wallenberg' is a competition for high school students. Teams from schools from all parts of Hungary, and also the Hungarian speaking parts part of the neighbouring countries, compete in their knowledge about the Second World War, the Holocaust and Raoul Wallenberg. The students also get an opportunity to reflect on more current issues such as racism, intolerance, and discrimination.

'The Cube' is a school project about Human Rights. Students create exhibitions on the theme of Human Rights inside large cubes, which are exhibited to the public. There are cubes in schools all around the world, and so far more than 10 Hungarian schools have taken part in this project.

The 'Young Courage Award' is an international award for young people that have shown courage in standing up for their convictions in their everyday lives. For example, by standing up to bullying, helping people in distress, or by advocating for minority rights.

The last time Raoul Wallenberg’s colleague and friend Per Anger spoke to him in January 1945, he asked Raoul why he was taking all these risks now that the war was soon over. Raoul replied:

„To me there’s no other choice. I’ve accepted this task and I could never return to Stockholm without knowing that I’d done everything humanly possible to save as many Jews as I could’.”

About the project

This site is as part of the Embassy of Sweden in Budapest’s continuous work to honour the legacy of Raoul Wallenberg and to promote human rights. The initiator of the site was Ambassador Dag Hartelius. A special thanks to the author, Raoul Wallenberg expert and member of the Swedish Academy Ms. Ingrid Carlberg who has reviewed the site’s historical content and provided many valuable comments.

The aim has been to make the text easy to read. Because of this some historical events have been simplified, and we use the modern names of some institutions. For example, the term ‘Embassy’ is used, instead of ‘Legation’ which was the actual name of the Swedish representation in Budapest during Raoul Wallenberg’s time. The site presents a selection of locations, and the aim has not been to write the full story of Raoul Wallenberg or to present every location connected to his legacy.

If not else stated the photo credits on the site belong to Oliver Sin and the Embassy of Sweden in Budapest. The aim is to continue to develop this site and we welcome your ideas and suggestions on how the map can be developed and improved. Please contact us via email: walkwithraoul.budapest@gov.se

Learn more about Raoul Wallenberg:

Books:

Raoul Wallenberg: The Biography: The Man Who Saved Thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Holocaust. Ingrid Carlberg, 2012.

The Hero of Budapest. The Triumph and Tragedy of Raoul Wallenberg. Bengt Jangfeldt, 2012.

Films:

Good Evening, Mr. Wallenberg, Kjell Grede, 1990.

The Lost European, József Sipos, 2015

More films available here.

Associations and organisations:

The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation

Raoul Wallenberg Academy (Sweden)

The Raoul Wallenberg Association (Hungary)

The Raoul Wallenberg House of Humanity Association (Hungary)

Created by

Krisztián Szabó, Attila Bátorfy, Andreas Attorps, Edina Tánczos

About the project

This site is as part of the Embassy of Sweden in Budapest’s continuous work to honour the legacy of Raoul Wallenberg and to promote human rights. The initiator of the site was Ambassador Dag Hartelius. A special thanks to the author, Raoul Wallenberg expert and member of the Swedish Academy Ms. Ingrid Carlberg who has reviewed the site’s historical content and provided many valuable comments.

The aim has been to make the text easy to read. Because of this some historical events have been simplified, and we use the modern names of some institutions. For example, the term ‘Embassy’ is used, instead of ‘Legation’ which was the actual name of the Swedish representation in Budapest during Raoul Wallenberg’s time. The site presents a selection of locations, and the aim has not been to write the full story of Raoul Wallenberg or to present every location connected to his legacy.

If not else stated the photo credits on the site belong to Oliver Sin and the Embassy of Sweden in Budapest. The aim is to continue to develop this site and we welcome your ideas and suggestions on how the map can be developed and improved. Please contact us via email: walkwithraoul.budapest@gov.se

Learn more about Raoul Wallenberg:

Books:

Raoul Wallenberg: The Biography: The Man Who Saved Thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Holocaust. Ingrid Carlberg, 2012.

The Hero of Budapest. The Triumph and Tragedy of Raoul Wallenberg. Bengt Jangfeldt, 2012.

Films:

Good Evening, Mr. Wallenberg, Kjell Grede, 1990.

The Lost European, József Sipos, 2015

More films available here.

Associations and organisations:

The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation

Raoul Wallenberg Academy (Sweden)

The Raoul Wallenberg Association (Hungary)

The Raoul Wallenberg House of Humanity Association (Hungary)